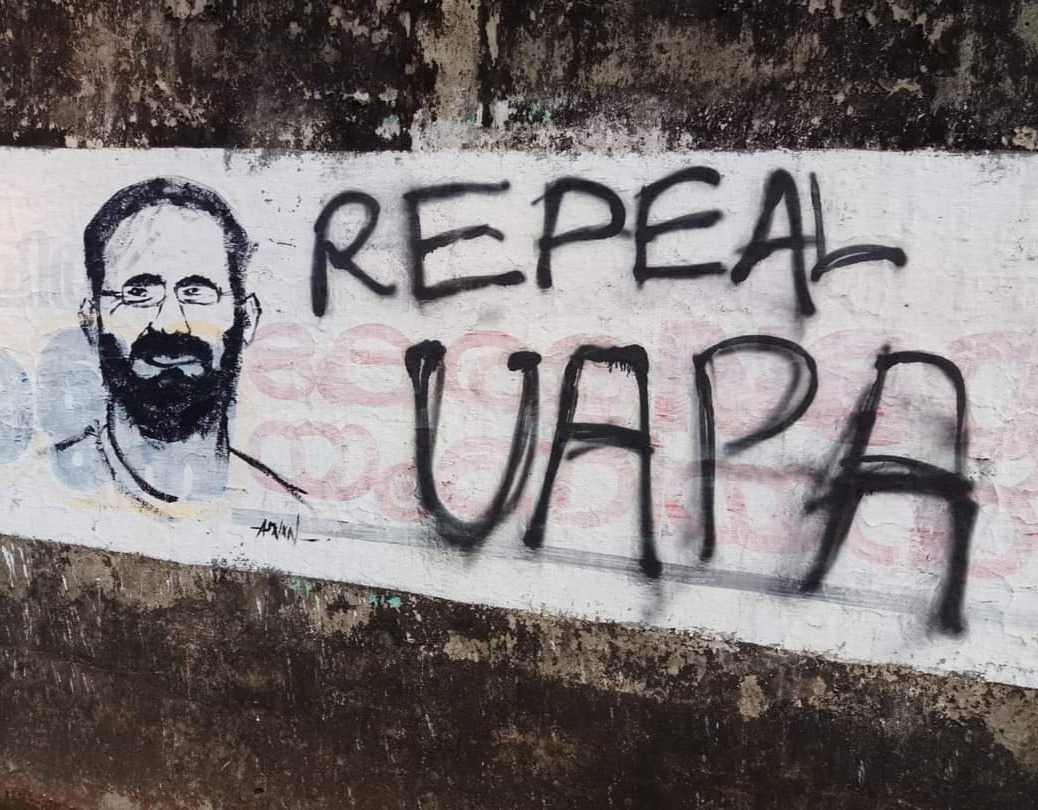

For 235 days, Malayalam journalist Siddique Kappan has been in a UP prison, charged with sedition and conspiracy to incite violence. The UP Police claim he is not a journalist, only posed as one while raising funds for terror. But over a decade of reporting, Kappan’s journalism tells a different story

Malappuram: It was 13 May 2021, Eid ul Fitr, the auspicious day after the sighting of the crescent moon that marks the culmination of a month of fasting during the holy Ramzan period.

As others in the lush, idyllic village of Poocholamadu, Vengara, in this northern Kerala district began their feasts and prayers, 37-year-old homemaker Raihanath and her three children, aged 17,13 and eight, sat quietly in their half-built, desolate home. Khadija, 90 years old and on her deathbed, waited for a glimpse of her son ‘Bava’, who the rest of the world knows as Siddique Kappan, 42, a Malayalam journalist in jail in Uttar Pradesh for 235 days now, eight months.

Kappan, a full-time reporter on retainer with the Malayalam news portal Azhimukham, was detained on 5 October 2020, by the Uttar Pradesh (UP) police while he was on his way to Hathras, in western UP, to report on the gangrape-murder of a Dalit girl.

Kappan is now accused under four sections of the Indian Penal Code, 1870, two sections of the Information Technology (IT) Act, 2008, and three sections of the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), 1967, charges relating to terrorism, outraging religious feelings, conspiracy and sedition. The bespectacled, bearded Kappan was incarcerated in the Mathura district jail. According to the UP police chargesheet, Kappan “posed” as a journalist from Thejas, a defunct Malayalam daily that served as a mouthpiece of the Popular Front of India (PFI), a radical Islamist outfit. The UP police suspect the PFI of stoking violence during the protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 (CAA) across the state. The UP Police has demanded that the PFI be banned. Over more than a decade as a journalist, Kappan reported on current affairs, crime and politics. He reported from Delhi, Kerala and the Middle East, and wrote features for many Malayalam media outlets, such as Thejas, Thalsamayam and Azhimukham, both as a staffer and a freelancer.

A computer engineer who was a teacher in a school in his hometown Vengara and later spent nine years in Saudi Arabia looking for greener pastures, Kappan returned home in 2011 when his father passed away. He decided to stay back to take care of his family and pursue, for the first time as a professional, his passion for journalism. After working on the news desk of Thejas in Kerala for some time, he moved to the paper’s Delhi bureau as a reporter.

According to the Free Speech Collective’s research paper ‘Behind Bars: Arrest and Detention of Journalists in India 2010-20’, 154 Indian journalists have faced arrest, detention, interrogation and show-cause notices between 2010 and 2020 for doing their job, and three of them—Kappan and Aasif Sultan (The Kashmir Narrator), who are in custody, and Prashant Rahi, who is sentenced to life imprisonment—were charged under the UAPA. States ruled by the BJP account for a large percentage of criminal cases against journalists; over 40% of the instances in 2020 alone.

A Decade Of Reporting

According to Raihanath, even during the nine years that he lived in Saudi Arabia, Kappan would write interviews and features for Malayalam dailies and magazines, including Malayalam News and Prasadhakan.

Over the phone from Delhi in later years, the couple would speak about his day, his work, the people he interviewed, and Kappan would sometimes express concern about the people he met who were in distress.

“When news of the Hathras incident broke, he was very emotional,” said Raihanath. “That girl was only a couple of years older than our son, he would say.” Their oldest son is 17, the Hathras victim was 19.

Kappan told her during one of his calls from prison later that he was trying to visit Hathras to talk to her family and file a story from there. He told her that he had hitched a ride in a car with a few students who were on their way to Hathras.

Kappan had worked as the Delhi reporter of Thejas daily until they shut down in 2018. Subsequently, he worked for daily newspaper Thalsamayam till November 2019, after which they also closed down due to financial constraints. Since January 2020, he had been reporting for Azhimukham. A press identity card issued by Thejas was still in his laptop bag, and he also carried an identity card issued by the Delhi Press Club. Kappan is also an office-bearer of a journalists’ trade union, of which he is a former secretary. Journalist KN Ashok, who was the editor of Thiruvananthapuram-based Azhimukham at the time of Kappan’s detention, recalled him as a seasoned journalist who knew his job.

He said Kappan was a regular contributor for them from Delhi, and “knows where he can find news”. Ashok said Kapppan had shown “genuine interest” in matters that affect people. He wrote about the Covid pandemic affecting migrant labourers, nurses, students, mediapersons and those engaged in sex trade, the anti-CAA protests, violence in Northeast Delhi, interviewed Tablighi Jamaat head Maulana Saad, lawyer-activist Prashant Bhushan, Delhi University professor G N Saibaba, political leaders K Muraleedharan and M K Raghavan and Malayalam writer Echmukutty, among others.

It would have been natural for Kappan to jump at an opportunity to go to Hathras, Ashok said. He texted Azhimukham desk around midnight of 4 October that he was headed to Hathras. The next evening, they tried to contact him to ask about the status of his report, but he couldn’t be reached. It was only later that they found out about the arrest.

On 6 October, Ashok, representing Azhimukham, filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court along with KUWJ to filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court to establish the credibility of Kappan’s journalistic career. In his affidavit, he said that Kappan is a retainer and a full-time contributor with Azhimukham and that he is a member of the Press Club and the Kerala Union of Working Journalists (KUWJ).

After the UP police and the Enforcement Directorate claimed that Kappan and others in the vehicle had links with the PFI and its student wing Campus Front of India, and accused them of money laundering to the tune of Rs 100 crore and conspiracy to incite violence, the PFI denied any link with Kappan and those named in the chargesheet. Raihanath said the claim by the UP Police and the ED that Kappan was raising funds for the PFI was false. “If so, would he carry ID cards?” she asked. “Had he been receiving funds, would we be living like this?” Their home is still under construction even after eight years; a brick-and cement-house that is not fully plastered.

One of Kappan’s last published features in Azhimukham was an interview of Jenny Rowena, PhD, wife of Delhi University professor Hany Babu, arrested by the National Investigation Agency in the Elgaar Parishad-Bhima Koregaon case. Hany Babu,imprisoned after being accused of Maoist links, like Siddique, is currently knocking on the doors of courts for fair medical treatment. To ensure that Kappan gets a fair trial, the Delhi unit of the KUWJ, of which Kappan is secretary, filed a habeas corpus plea on 6 October. The petition, which was supposed to be disposed of on 9 March, 2021, has not been disposed of yet though it was listed seven times. PK Manikandan, a close friend of Kappan and a member of KUWJ, called the accusation of a PFI link “ridiculous”. He said a journalist who works for a media house need not believe in its politics. “At Thejas, Kappan was an employee who got paid for his job. In fact, Kappan is someone who has written a critical piece on the PFI later.”

Kappan at a protest organised by the Kerala Union of Working Journalists.

In February, Kappan was granted a conditional five-day bail to meet his mother. Senior counsel Kapil Sibal, representing the KUWJ in the SC, argued that the case pertained to a ‘matter of personal liberty’, referring to the case of Republic TV editor-in-chief Arnab Goswami, who was granted bail within a week of his arrest on grounds of personal liberty in a case of abetment to suicide. The SC observed on 2 December, 2020 while granting bail to Goswami that ‘every case is different’.

Chained To Cot, Given A Bottle To Urinate

Kappan, a chronic diabetic for more than 15 years, must have insulin twice a day. The food in Mathura jail caused him to suffer digestive problems, leading him to survive on cucumber and curd, even during Ramzan, the month of fasting.

He was lodged in an overcrowded cell with almost 75 inmates and one bathroom. Jail authorities would let him call home once in a while. During one of his calls home in April, he told his wife that over 50 prisoners in the prison were Covid positive.

On 21 April, Kappan, who had been suffering from diarrhoea, body pain and fever for a few days, collapsed in the bathroom and suffered injuries to his chin and leg. Police then took him to the Medical College Hospital in Mathura, where he tested positive for Covid-19.

On 24 April, he managed to call Raihanath from the hospital, using somebody else’s phone. “Only then did I learn that he was chained to a cot and was given a bottle to relieve himself,” she said. “How low can people stoop? How can this be endured?” Raihanath recalled that Kappan simply wanted to return to the prison, which was better than being in hospital. When this news emerged, Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan wrote to his UP counterpart Yogi Adityanath, seeking expert and humane care for Kappan. As many as 11 MPs from Kerala, including K Muralidharan, K Sudhakaran, ET Mohammed Basheer, NK Premachandran and PV Abdul Wahab, wrote a joint letter to the Chief Justice of India seeking immediate intervention in the matter. The SC intervened, directing the UP Government to shift Kappan to AIIMS, Delhi, for adequate and effective medical assistance. Barely a week after moving Kappan to AIIMS on 30 April, the UP police took him back to Mathura jail before recovering and without being allowed to meet his wife and son who waited outside the hospital for seven days. Kappan with his eight-year-old daughter Mehnaz.

Advocate Wills Mathews, who represents KUWJ, called it “humiliating treatment”.

“Kappan’s wife and son travelled all the way from Kerala, leaving two children, aged 13 and eight, and an ailing mother, hoping to talk to him in person,” he told Article 14.

The mother and son waited for a week, seeking permission from Shailendra Kumar Maitrey, senior superintendent of Mathura district jail. It never came. They visited AIIMS every day, but the police did not even provide information on Kappan’s condition to Raihanath, nor information about his discharge.

In an affidavit in the SC filed on 28 April, the jail authorities said Kappan had tested negative. But on being tested in jail, he tested positive for Covid once again on 2 May.

Raihanath

filed a contempt notice against the UP government for non-disclosure of Kappan’s condition in the court. “We fear that this non-disclosure was due to the fear arising out of your statement that Kappan is Covid negative in the affidavit,” it read. There was no response to the notice until the end of May.

Raihanath and her son went to Mathura, hoping to meet him in jail. But all requests were rejected; a representation given to the superintendent was refused citing that “there is no provision in the UP jail manual for the same”.

On 8 May, en route home, Raihanath

posted on Facebook, ‘Returning from Delhi, without meeting him... The legal fight will continue, till truth triumphs.’

‘Is Hathras Not In India?’

Senior journalist NP Chekkutty, chief editor of Thejas when it shut down, knew Kappan for years as the latter struggled to keep a job, hit by the financial crisis.

“He was struggling hard for years to build a home and take care of his family. A journalist who has been shuttling between unpaid jobs, someone who had only Rs 200 when arrested, who was on his way sharing a car with three others on his way to work–does he sound like a terrorist?” Chekkutty, who is based in Kozhikode, Kerala, said citizens have the right to travel anywhere in the country.

“Is Hathras not in India?” he asked.

Chekkutty heads the Siddique Kappan Solidarity Forum, an organisation formed by Kappan’s acquaintances to ensure that the issue doesn’t lose steam. Over six months, they have organised online and offline events across Kerala. Chekkutty said the case is a blatant violation of human rights, liberty and press freedom.

D Dhanasumod, a former journalist with Kochi-based channel TV New, who shared his office building in Delhi with Thejas, remembered Kappan as a soft-spoken person with a warm smile. “Kappan is a man who showers everyone with love and would never hurt a fly,” he said. He remembered occasions when they chatted for hours over tea on Jantar Mantar Road in Delhi, sometimes long after midnight.

Kappan was in a deep financial crisis and, apart from reporting, also undertook translation work and content writing to earn money, said Dhanasumod. “Despite the struggles, he always wears that beaming smile on his face,” he said.

Dhanasumod was an office-bearer of KUWJ and had participated in many protests along with Kappan for better working conditions for journalists and implementation of wage board recommendations.

Kappan’s friends said he had no political affiliation. “None of us ever saw him attending any political event. No organisation is backing him even in this fight,” said Manikandan.

According to Manikandan, proof that Kappan didn’t ‘pose’ as a journalist is that he has a Press Club of India membership and is a member of the Delhi Union of Journalists, a trade union.

Several from social, political and literary circles expressed support for Kappan too.

When the Editors’ Guild of India issued a statement saying it was

deeply disturbed by the custodial torture of Kappan, Congress chief Rahul Gandhi and former SC judge Markandey Katju added their voices to the matter.

“Being a journalist and a Muslim is a deadly combination in India,”

tweeted Katju, while

Rahul promised “full protection and medical support” for Kappan.

Noted journalist P Sainath, in an interview to Madhyamam, a Malayalam daily, said, “The Siddique Kappan case is one of the most outrageous, shameful and unpardonable abuses and action against a journalist that I have seen in 40 years in the profession.”

The KUWJ sees Kappan’s arrest as an issue of democracy and free press. “This plight could fall upon any journalist, any day. Our fight is for the right to work freely,” Manikandan said.

The Fight Continues

On 3 April 2021, the UP Police filed an over 5,000-page-long chargesheet in the Mathura district court last, charging eight persons including Kappan under sections 153(A) (promoting enmity between different groups on ground of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language), 124(A) (sedition), 295(A) (deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings) and 120 (B) (criminal conspiracy) of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC), along with Sections 17 (raising funds for terrorist act) and 18 (conspiracy) of the UAPA, and Sections 65 (tampering with computer source documents), 72 (breach of confidentiality and privacy) and 78 (power to investigate offences) of the IT Act.

“All the charges are false, Kappan is framed,” said advocate Mathews. He said the money transactions to which the charge sheet devotes 20 pages are sums of Rs 20,000 and Rs 25,000 received in his bank account in two months—his monthly salary.

Mathews spoke to Kappan in court on the day the charge sheet was filed. He was weak, but confident and fearless. “I am innocent, and hence fearless, Kappan told me,” Mathews told Article 14.

The SC intervention, public interest and the relentless fight by Raihanath have ensured Kappan better facilities in jail.

Kappan recently contacted Raihanath and told her he was better. He was in the isolation ward of the hospital. He needed a dental checkup and his blood sugar levels remained high, but he was reportedly getting better food and regular medicines, including insulin shots.

“They shouldn’t have shifted him from AIIMS without him getting better,” said Raihanath. “They told SC that he was out of Covid, but I can’t believe that a person with serious medical issues would turn negative in six days and again turn positive in another six days after he is lodged back in prison.”

A phone call to the Mathura district jail yielded little information. An official merely said Kappan was in better health. “He is in regular contact with his family and lawyer,” the official told Article 14.

Mathews said he had not been able to contact Kappan in jail, but added that the current focus was on ensuring he stayed alive and healthy. He said they had stalled UP police attempts to take him to Lucknow for scientific tests, insisting that voice sampling, brain mapping, narco analysis, polygraph or any other means of collecting evidence can be done at the CBI headquarters in New Delhi or in Chandigarh but not in UP’s forensic establishments.

Mathew said they feared it would be difficult to protect Kappan if he is taken anywhere other than Delhi for scientific tests. “If a UAPA accused is gunned down by the police saying he tried to escape, we can’t do anything,” he said.

On 25 May, a reminder to their contempt notice was filed as it had yielded no response. On 31 May, Raihanath filed a bail application in Mathura courts before the district judge, an additional district judge and a special judge, citing Kappan’s poor health, his mother’s deteriorating condition, and the lack of evidence against him.

Raihanath confirmed that Kappan tested negative for Covid-19. His mother remains critical. She has developed bedsores and talks little. While she used to ask for him earlier, now she just cries, said Raihanath.

“I can’t tell her about her son, or my husband about his mother’s health,” she said. “It’s painful; I can only pray.”

For Raihanath, the past eight months have been harrowing and testing. When she got married to Kappan, she had been a naïve 19-year-old with no exposure to the real world.

“I knew nothing,” she said. “My world was him and my family. It came crashing down one day.”

Dealing with the legal matters and grief, Raihanath said she could not properly take care of her children’s studies and her ailing mother-in-law. She had to fly to Delhi without knowing the language or the people.

“Long back, when he told me about the condition of (Delhi University professor) GN Saibaba when he

interviewed his wife and daughter, he said it hurt to listen to them,” she said. The terror-accused paraplegic professor with 90% disability is serving a life term in a Maharashtra jail.

“I never thought I would experience their agony months later,” said Raihanath. “But I am determined to fight. Whatever happens, I have to free him.”

Published in Article 14 on June 2, 2021

.jpg/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=w:1160,h:1781)